Application virtualization is an umbrella term that describes software technologies that improve portability, manageability and compatibility of applications by encapsulating them from the underlying operating system on which they are executed.

A fully virtualized application is not installed in the traditional sense, although it is still executed as if it were. The application is fooled at runtime into believing that it is directly interfacing with the original operating system and all the resources managed by it, when in reality it is not.

In this context, the term “virtualization” refers to the artifact being encapsulated (application), which is quite different to its meaning in hardware virtualization, where it refers to the artifact being abstracted (physical hardware).

So Wikipedia says.

In layman terms, application virtualization is “I want to run a third party application without it requiring installation”. Probably you know it as “portable application“.

The trivial case

If we talk about Windows applications, for simple applications, application virtualization amounts to copying the .exe and any required DLL to some folder, then running the application from that folder.

Easy, huh?

Well, no.

Registry keys

Many applications add keys to the registry and will not run without those keys. Some even require other files, which are created in AppData, CommonAppData, etc.

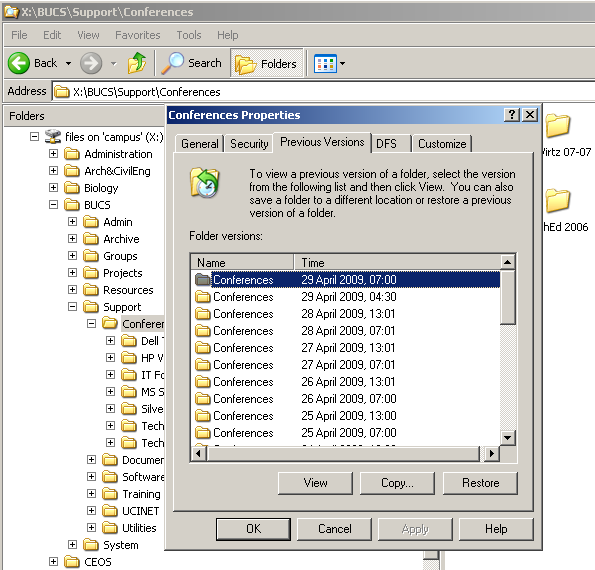

To solve this kind of dependencies, application virtualization software packages such as VMware ThinApp, Microsoft App-V and Citrix XenApp monitor the registry and the filesystem for changes. To do so, they require an “application virtualization preparation” procedure. It’s like you have a clean virtual machine, take a snapshot, then install the application, take another snapshot, and compare them.

You could achieve more or less the same result for free by using FileMon + RegMon + RegShot.

Of course I am simplifying more than a bit here 🙂

Common files

Then there is the problem of file redirection.

The whole point of application virtualization is to be able to run the application without installation. But if this application’s setup installed files in CommonAppData (or the application creates them), how do we force the application to look for them in our “virtualized application folder”?

The technique usually involves generating a small .exe launcher that:

- Sets a special PATH that looks where we want first

- Uses hooking, DLL injection and some other low level tricks to force system calls to look into the places we want before (or even instead of) they look into the standard places

- Registry emulation (in combination with hooking and DLL injection) to make sure those registry keys are taken from the registry in the sandbox instead of the actual registry

- And more

In a way, we are cracking the application.

Cross-platform

What I have described above are the required steps to virtualize an application if the target platform (where the application is going to be run) is the same as the host platform (where the application virtualization was performed). For instance, if we are virtualizing the application on Windows XP SP3 32-bit and the application will run on Windows XP SP3 32-bit.

Even if the steps described above look complex to you (they are), that’s the simple case of application virtualization.

If the target platform is a different version (for instance, the app virtualization takes place on Windows XP 32-bit, while the target platform is supporting also Windows 7 64-bit), then it gets more complex: probably many Windows DLLs will need to be redistributed. Maybe even ntoskrnl.exe from the original system is required.

In addition to the serious problem redistribution poses in terms of licensing to anybody but Microsoft App-V, there is the technical side: how do you run Windows XP SP3 32-bit ntoskrnl.exe on Windows 7 SP1 64-bit? You cannot, which makes some applications (very few) impossible to virtualize.

Device drivers

The more general case for “impossible to virtualize applications” (we are always talking about application virtualization here, not full virtualization or paravirtualization) is device drivers.

None of the application virtualization solutions that exist so far can cope with drivers, and for a good reason: installing a driver requires administration permissions, verifying certificates, loading at the proper moment, etc. All of that needs to be done at kernel level, which requires administration permissions, thus defeating the point of application virtualization. Then there are the technical complications (the complexity of the implementation), and the fact that drivers assume they run with administration permissions, therefore they may perform actions that require administration permissions. If that driver is also app-virtualized, it will not run with administration permissions.

One possible remedy to the “driver virtualization problem” would be to implement a “driver loader process” that requires installation and will run with administration permissions. Think of it as the “runtime requirement” of our application virtualization solution.

I know, I know, it sounds contradictory: the whole point of my app virtualization software solution is to avoid application installation, yet my app virtualization solution requires a runtime installation? We are talking about a one-time installation, which would be perfectly acceptable in a business environment.

But why all this!?

You may wonder why this braindump.

The reason is the job that pays my bills requires virtualization. Given that we need driver support, we resorted to VirtualBox but we run a lot of instances of the applications we need to virtualize, which means we need a lot of Windows licenses for those virtual machines. Worse: we cannot know how many Windows licenses we need because the client may start any number of them and should not notice they run in virtual machines! Even worse: Microsoft have a very stupid attitude in the license negotiations and keep trying to force us to use Windows XP Mode and/or Hyper-V, which are not acceptable to us due to their technical limitations.

So it turned on the “think different switch” in my brain and I came with a solution: let’s port Wine to Windows and use it to virtualize applications.

The case for a Wine-based Application Virtualization solution

Crazy? I don’t think so. In fact, there would be a number of advantages:

- No need for Windows licenses

- No need for VirtualBox licenses

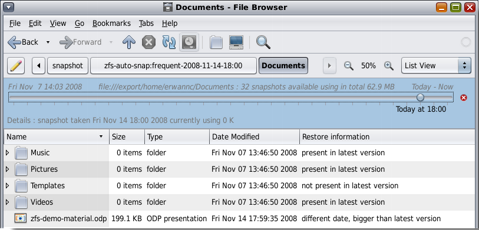

- Wine already sandboxes everything into WINEPREFIX, and you can have as many of them as you want

- You can tell wine to behave like Windows 2000 SP3, Windows XP, Windows XP SP3, Windows 7, etc. A simple configuration setting and you can run your application the environment it has been certified for. Compare that to configuring and deploying a full virtual machine (and thankfully this has been improved a lot in VBox 4; we used to have our own import/export in VBox 3)

- No need to redistribute or depend on Microsoft non-freely-redistributable libraries or executables: Wine implements them

- Wine has some limited support for drivers. Namely, it already supports USB drivers, which is all we need at this moment.

Some details with importance…

There are of course problems too:

- Wine only compiles partially on Windows (as a curiosity, this is Wine 1.3.27 compiled for Windows using MinGW + MSYS)

- The most important parts of wine are not available for Windows so far: wineserver, kernel, etc

- Some very important parts of wine itself, no matter what platform it runs, are still missing or need improvement: MSI, support for installing the .NET framework (Mono is not enough, it does not support C++/CLI), more and more complete Windows “core” DLLs, LdrInitializeThunk and others in NTDLL, etc

- Given that Windows and the Linux kernel are very different, some important architectural changes are required to get wine running on Windows

Is it possible to get this done?

I’d say a team of 3-4 people could get something working in 1 year. This could be sold as a product that would directly compete with ThinApp, XenApp, App-V, etc.

We even flirted with the idea of developing this ourselves, but we are under too much pressure on the project which needs this solution, we cannot commit 3-4 developers during 1-2 years to something that is not the main focus of development.

Pau, I’m scared!

Yes, this is probably the most challenging “A wish a day” so far. Just take a look at the answer to “Am I qualified?” in Codeweavers’ internships page:

Am I Qualified?

Probably not. Wine’s probably too hard for you. That’s no insult; it’s too hard for about 99% of C programmers out there. It is, frankly, the hardest programming gig on the planet, bar none. But if you think you’re up for a real challenge, read on…

Let’s say, just for the sake of argument, that you’re foolish enough that you think you might like to take a shot at hacking Wine. […]